Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash

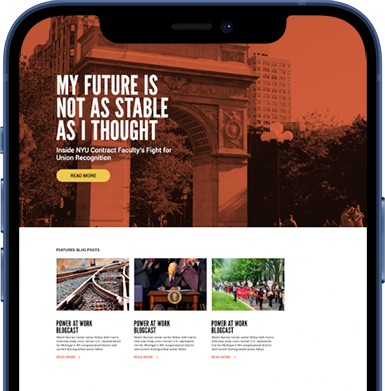

When I talk with fellow workers, organizers, and union leaders across the country, I often hear the same two feelings expressed in the same breath: excitement and frustration. People see energy building in places we never expected—baristas, warehouse workers, graduate employees, workers in retail and tech who are standing up in ways that felt impossible just a few years ago. The media has rediscovered labor. Young workers in particular are organizing at rates we haven’t seen in decades. Public approval of unions is the highest it has been since the 1960s.

And yet, when you look at the national numbers, union density – the percentage of American workers represented by a union – remains unchanged. Even in years when unions bring in hundreds of thousands of new members, the overall workforce grows faster. The percentage of workers represented by a union continues its long slide. It’s a contradiction that everyone in the labor movement feels: momentum on the ground, stagnation in the statistics.

This contradiction is what led my colleagues Michael Wallace, Andrew Fullerton, and me to take a deeper look at why union density has declined so sharply and why it has been so difficult to reverse. For a recent study, we collected and analyzed nearly 60 years of data—every year from 1964 through 2023, in every state in the country. We wanted to understand not just what happened, but why it happened, and what that might mean for workers today.

Looking Beneath the Surface

Most explanations for union decline focus on familiar culprits: the loss of manufacturing jobs, changes in labor law, aggressive employer opposition, and broader political shifts. All of those factors matter and have indeed contributed to the decline in labor’s power. But we suspected something additional was happening—something that older research had not fully captured. So, we expanded the scope of our study to include two long-term transformations in the U.S. economy that we believe sit at the heart of today’s challenges.

The first is financialization. Over the last several decades, the center of gravity in the American economy has shifted from production to finance. Corporations that once reinvested profits into workers, equipment, and long-term stability are now pushed to deliver immediate returns to private equity firms, hedge funds, and shareholders. Decisions are filtered through the lens of short-term financial gains. The easiest way to deliver those gains is to cut labor costs—outsourcing, subcontracting, resisting unionization, pushing for anti-labor legislation, and squeezing workers wherever possible.

The second is precaritization, or the spread of insecure, unstable, poorly paid jobs. Gig work, temp work, part-time work, subcontracted work—millions of jobs today offer fewer protections, fewer hours, and fewer opportunities to build a stable life. This transformation of the standard job creates precarity because it circumvents so many of the standard labor protections and benefits that were won during a time when jobs were overwhelmingly full time, permanent, and long-term. This transformation also makes organizing more challenging. Workers have lower bargaining power, higher turnover, and a constant fear of retaliation.

Photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash

Together, these two forces shape the terrain on which unions fight. The policies did not change overnight; they are long-term shifts in how the American economy works. Yet, to our surprise, their impact on union density had never been systematically examined at the state level across multiple decades. We decided it was time to bring them into the analysis.

To measure financialization, we looked at the size of the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors in each state's economy, how much workers in that sector earned, and how concentrated banking assets had become. To measure precaritization, we looked at the percentage of workers employed by temporary help agencies, the ratio of total jobs to employed people (which captures part-time and multiple jobholding), and the rate of labor exploitation in manufacturing (how much value workers created versus what they were paid).

What Six Decades of Data Show

Our findings demonstrate that union decline is not driven by a single cause. Instead, it reflects a combination of structural pressures that vary across time and place.

Financialization and precaritization both have strong negative effects on union density. That remained true even when we controlled for other factors like right-to-work laws, unemployment levels, political party control, and the industrial makeup of each state. States with more financialized economies saw union density fall faster. States with more precarious work did too.

These effects grew stronger during the era associated with neoliberal policy—from roughly 1981 to the present. Deregulation, attacks on labor standards, tax policies that incentivized stock buybacks, and the weakening of public institutions all created a climate that magnified these forces.

Another piece of the story is regional. The South has long been hostile terrain for unions, with lower wages, weaker labor laws, and a political environment shaped by a history and legacy of racial inequality and employer dominance. In places where union density was already low, the added pressures of financialization and precaritization had less visible impact—not because the forces were irrelevant, but because the floor was already so low. Outside the South, however, these forces helped hollow out strongholds that once formed the backbone of the labor movement.

The period surrounding the Great Recession offered one surprising twist. For a brief time, the relationship between financialization and union density shifted. Because the financial sector itself was in crisis, its power over employer behavior weakened. At the same time, the public conversation turned sharply toward inequality, Wall Street greed, and the struggles of the working class. Movements like Occupy Wall Street amplified these themes. The overall decline did not reverse, but the downward pressure eased for a moment. It was a glimpse of how quickly the political winds can shift—and how powerful public sentiment can be.

What This Means for Workers Today

For union members and leaders, one of the most important takeaways is that workers are not imagining their difficult challenges: Organizing really is harder now than it was a generation ago. The obstacles are not simply bad bosses or weak laws—though those matter too. The terrain has been shaped by decades of economic transformation that have made workers less secure and corporations more powerful.

"2011 AFGE Legislative Rally", by AFGE, CC BY 2.0

But the fact that workers are still organizing, and doing so successfully in some of the toughest environments, says something powerful about the moment we are in. The same forces that have weakened unions have also made millions of workers hungry for change. Precarious work breeds instability, stress, and exhaustion, but it also breeds anger—and a desire for dignity. Financialization has made inequality painfully visible, creating a broader public understanding of the stakes. Young workers who came of age during and after the Great Recession are more pro-union than any generation in half a century.

Another major lesson is that policy matters. The rise of financialization and precaritization was not inevitable. It was the result of political decisions—from deregulating the financial sector to weakening labor protections to encouraging corporate consolidation. The decline of unions followed those decisions, not the other way around. If policy choices helped get us into this situation, different policy choices can help get us out.

Strong labor laws remain one of the most effective tools we have. While the current federal government is unlikely to enact pro-worker labor law reform, there is great variation across the states. States that protect and promote collective bargaining rights have higher union density. States that weaken those rights see membership fall. Public-sector bargaining laws in particular have spillover effects that strengthen unions across the board. None of this is accidental. Political power is labor power.

A different future—one defined by worker power, stability, fairness, and dignity—can be rebuilt either rapidly as was done through the militancy that characterized the 1930s, or slowly over decades the way capital dismantled worker power since the 1980s. Either way, it will not be easy. It will take new strategies that empower workers in the workplace but also in the political arena to change laws in a way that reign in financial power and protect and strengthen workers’ rights.